how can i help parents escape from situations where they feel trapped or unable to decide what to do?

Impossible situations | Conflict of message | Conflict of motive

“I repeat myself, then scream. He hits me. I don’t want him to think I’m always shouting.” (Parent, before toddler clinic)

You can download these resources and the worksheet as a separate file here (the link is provided again below).

The third pathway for expertise looks at specific expertise and skills involved in helping parents who find themselves torn between two different actions of behaviours. This kind of 'situation impossible' comes up frequently in parenting, and the study found a consistent principle underpinning effective interventions that helps parents break away from feeling trapped, and able to regain control of the situation and their decision-making. This principle is based on the Vygotskian concept of double stimulation (it thus comes from the same theoretical roots as the zone of proximal development, which was used in relation to challenging effectively).

Parents often find themselves torn between two different courses of action. They get stuck because there is no clear way to decide what to do. We found that some helpers used a very special technique to help parents in these impossible situations. This technique was a crucial component of the evolving art of impactful partnership. While the principle underpinning it is consistent, the details are different every time and require helpers to attune their intervention to the specifics of a particular problem and its context.

First, recognise

Conflicting messages

Then, discern

Conflicting motives

Escape through use of

external signposts or Action tools

Double check this is the final version

Key concept: double stimulation

The idea of double stimulation comes from Vygotsky [1,2,3]. It explains how people escape from situations where they are trapped between two equally balanced ways of acting. The dilemma is called the first stimulus: a problem that grabs our attention. The solution rests in finding and using an appropriate second stimulus.

A second stimulus can be an object, an bodily action, or even an idea. What gives something special status as a second stimulus is that it changes the situation: what was an impossible decision becomes possible. The person has taken back control. We might do this by counting out loud to three when we have to take a medicine that we know tastes unpleasant.

Parenting involves many dilemmas where it isn’t easy to decide what to do, because love for a child and protective instinct often suggest contrary ways of acting.

In such situations, helpers can make an impact by finding appropriate second stimuli – what we call ‘external signposts and action tools’.

This technique can be understood as an example of what Vygotsky called double stimulation ([1], see key concept box). The version of it presented here is based on a recently developed conceptual model [2]. Double stimulation is another way in which helper expertise becomes productively entangled with what parents know and with their immediate situation. Resolving the impossible situation is an example of a small thing that has a big effect: the solutions are typically everyday objects, or simple ideas, but they have a significant effect in creating a way out of impossible situations for parents.

This technique works its magic by diagnosing and addressing the true cause of the problem. This has nothing to do with parents lacking love for their children, or not wanting what is best for them. It is about needing additional tools to enable parents to feel in control rather than trapped between a rock and a hard place.

These tools can be ideas, actions, or household objects. They play a special function in providing a means to escape dilemmas. This is a mind-expanding process because the meaning of everyday tools and ideas changes (expanding interpretations), and it is linked to changing the basis for parents’ responses to difficult situations (expanding actions).

What do impossible situations look like?

Impossible situations are more common that we might think; we found many examples in our study. Some can be quite serious, others less so. Regardless, if they aren’t addressed, problems can develop and get worse.

Examples of impossible situations:

Wanting to cuddle a misbehaving toddler but also wanting to take a firm stance and not reward aggression with attention

Wanting to be with a child struggling to fall asleep but finding it stressful when she cries

Wanting to try out new strategies but finding it easier to go back to normal

Wanting to protect the child from viruses but also wanting to build her immunity and to socialise.

What is common to all these situations is that both options reflect positive desires. It is not a choice between good and bad, but an impossible choice between two versions of doing the right thing.

Parents find themselves pulled in opposite directions. When this happens, they can be at the mercy of the situation, rather than feeling they are in control of their decisions and actions.

The solution requires a particular kind of intervention in which special kinds of expertise are needed.

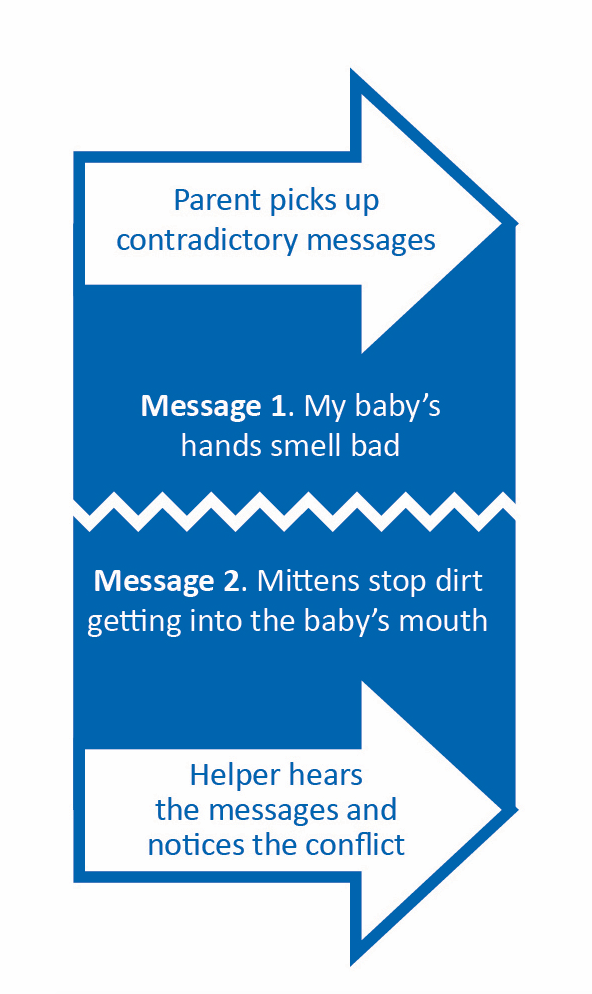

The diagram above shows an example involving a mother who found it hard to remove mittens from her child’s hands, even though she was disturbed by their smell.

First, recognise conflicting messages

The process begins by recognising the parents' difficulty parents as an impossible situation.

Those involved have to understand that there are conflicting messages. These messages are stimuli – something that parents notice and want to respond to.

Helpers have to identify conflicting messages as an indicator of impossible situations.

Such messages can come directly from children, as when they rub their eyes showing tiredness, or lash out in anger. They can also come from parents, as when they feel their heart racing when they are anxious, or from their current ideas about parenting.

These conflicting messages can also be indirect, as when nappies tell us something about a child’s nutrition, or smells tell us about bacteria on a child’s mittens.

The key point is recognising that the messages convey opposing needs: do this versus do that.

In the diagram, the messages are the smell from the mittens (take them off!), and the idea that mittens keep children safe by stopping them putting their hands in their mouth (keep them on!).

Then, recognise underlying conflicting motives

What makes the situation impossible is that these messages are each tied to deeper motives. These motives are also in conflict, pulling the parent in opposite directions.

In order to find an escape, the helper has to discover these conflicting motives and recognise that they are both legitimate.

Sometimes these motives are relatively obvious. Sometimes the helper needs to ask why something matters to a parent. Making the connection from messages to motives is important, not only because it is needed to address the true cause of the problematic situation, but because it is a way for the helper to show they are working on parents’ terms – with what matters to them.

Once these motives are uncovered, the true cause of the impossible situation can be discovered: we understand why it is so difficult for the parent to decide what to do, that there are good reasons why she is stuck.

In the diagram, the motives are to stop the smell and protect the child from germs. Both are legitimate, but they don’t help decide what to do.

Escape through use of external signposts and action tools

What the helper does next is crucial. The escape relies on suggesting one or more action tools that enable the parent to feel back in control. These shift attention from the problem to the nature of the solution, and as such they act as signposts.

Such action tools were found to be most secure and effective when they were ‘external’ in some way. This means the escape to the impossible situation was not a question of asking parents to dig deep or change something about their core values and motives.

Rather the action tool was a cue or prompt from the external environment, or something they could do physically, acting outwards from their body onto the world (like talking aloud, particular gestures, movements etc.).

This externality is important because it shifts the burden of the decision, away from an impossible dilemma to a way of acting via something else.

These action tools can be things like deep breathing to help parents calm down and go back to their distressed child. They can be based on rules or patterns in practices, like those in Parent-Child Interaction Therapy around giving commands.

“I’m just not the shouty mum any more.” (Parent, after toddler clinic)

We found that action tools were not always easy for parents to use, or were not immediately acceptable. So, the most effective helpers realised this and worked to secure parents’ commitment to using the action tools.

In the diagram, the parents' action tools included empathising with the child (to realise constant mitten-wearing could be frustrating), observing other children’s (bare) hands, and asking her partner

for help.

Using the impossible situation resources to enhance your practice

The main worksheet is designed for practitioners to reflect on their practice. There is also a version that you may find helpful to use in your actual work with families - this contains the main figure and some key prompts.

Worksheet 10 - Impossible situations (to print on A4 and complete by hand)

Combined resource and Worksheet (can be completed in the digital file)

References

[1] For more details of how this works in child and family services, see Hopwood, N., & Gottschalk, B. (2017). Double stimulation “in the wild”: Services for families with children at risk. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 13, 23-37. doi:10.1016/j.lcsi.2017.01.003

[2] For a full explanation of the theoretical model of double stimulation see Sannino, A. (2015). The principle of double stimulation: a path to volitional action. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 6, 1–15. doi:10.1016/j.lcsi.2015.01.001

[3] For a widely available translation of a relevant part of Vygotsky’s original work see Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: the development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.