what are the essential ingredients of impactful partnership?

You can download these resources and the worksheet as a separate file here (the link is provided again below).

The first aspect of the essence of partnership focuses on the essential ingredients: what has to be there for impacts to be realised.

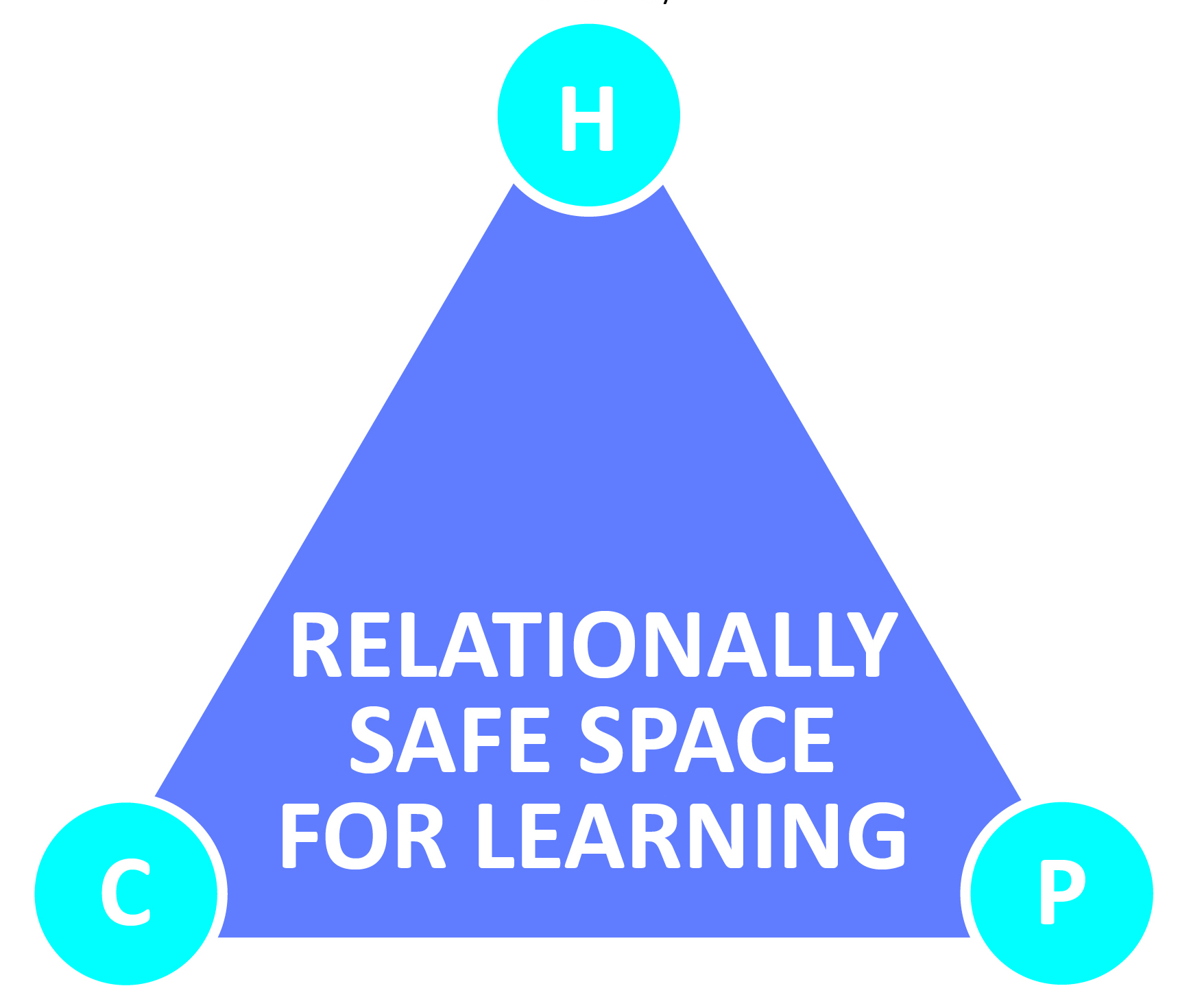

Help, challenge, and possibility are essential to impactful partnership.

These were present in every example of change we studied. If any one of them is missing, lasting positive change is put at risk.

They are also the essence of impactful partnership – they are what make it.

All three of these ingredients are connected with partnership as mind-expanding: help, challenge and possibility all involve exploring new ways of understanding, acting, and relating to others.

These essential ingredients are represented in the triangle diagram below.

The essence of impactful partnership

Help, challenge and possibility - all in a relationally safe space for learning

Possibility

Seeing things newly for parents, children and families

safe space for learning

The essential context in which help, challenge and possible must be located

Key concept: safe space for learning

While help, challenge and possibility are essential, they have to occur in a safe space for learning. Safe spaces are made through the relationships helpers have with families, and are grounded in trust, openness and honesty. These are not just relationships to be in for their own sake, but for learning. They have to be safe for parents, children and those helping them to learn together. See more below

help

Help must be acceptable, affirming, and subtle as well as overt

Impactful partnership requires helpers to assist parents in a number of ways. This is not about helpers rescuing or ‘carrying the baton’ for parents but them working with parents in ways that makes things possible. We found the following kinds of help were often needed:

Practical – appointments, providing transport, accessing other assistance

Strategic – suggesting things to do (differently) as a parent

Emotional – listening, being empathetic and not judging

Relational – connecting families with others in the community and helping parents learn new ways of being in a relationship with others, including those helping them.

However, what our findings show is that it isn’t just a question of offering the right kind of help. Help has to be both acceptable to parents and affirming of them in positive ways.

Parents don’t always find asking for help or accepting help from others easy. It can make them feel needy or dependent . Help in an impactful partnership has to be offered in a way that assists parents to feel comfortable. Normalising the idea of getting help is an effective way of doing this.

Sometimes help is obvious, meaning it is talked about in detail together. Offering referrals to other services, suggesting parenting strategies, or joining in activities with children are examples of obvious support.

“She’s helped me get him into speech because his pronunciation has always worried me…she’s rung them up and given me a lift down there.” (Parent)

Help can also be subtle. This does not mean hidden or stealthy. It means that suggestions or assistance are presented quietly or as a part of obvious support. For example, the community in a Child and Family Centre (TAS) made a photo book as a way to help parents take a child’s perspective by suggesting they put words in speech or thought bubbles (see building impactful partnership for more about obvious and subtle intervention).

Acknowledging and affirming that parents have already done something positive by seeking help is powerful too.

challenge

Challenge must address the tough stuff, the elephant in the room, and can be confronting

Impactful partnership means helpers need to go beyond being nice. It inevitably involves complex and layered challenges. Participants in our study described this in terms of addressing the tough stuff, talking about the elephant in the room, and sometimes needing to confront parents with difficult ideas, including being honest about the fact that they will be actively involved in bringing about change and it isn’t going to be done for them.

Challenge is delicate because it can easily make parents feel overwhelmed, or confirm a (false) idea that they are failing at parenting.

Challenge goes the other way too: parents can challenge helpers. One example of challenge in both directions is in giving and receiving honest feedback. If the way of working together needs to be adjusted, it is crucial that this is explicitly discussed, but raising such matters can be difficult.

Challenge works best when it is just ahead of what parents are already doing.

We found challenge works best when it is just ahead of what parents are already doing. In other words, it is achievable with the right support. Parents also need to understand why taking on a particular challenge is necessary in relation to something that matters to them.

Helpers in our study challenged parents in relation to the following aspects of parenting and change:

Technical understandings, for example, of children's sleep cycles

Parents' actions, responses and practices, for example, why shouting at a child may not be helpful

Safety concerns, for example, objects in a cot that may pose a danger

Parents' understandings of themselves, for example, that they are not failing or hopeless

Parents' commitments to self care, for example, that it is okay to look after themselves properly

Parents' understandings and expectations of the change process, for example, that it will take time and there will be ups and downs along the way (no quick fixes!)

The parent-professional partnership itself, for example, how the work together is going and what needs to change in the process.

Failure to address challenges in any of these aspects can undermine impactful partnership. Challenging parents in this way doesn’t have to mean they feel judged or criticised. The section on Pathways for Expertise gives a framework that shows how challenge can affirm parents as positive agents of change.

possibility

Possibility is about the self (as parent), the child, the family - through seeing things differently

Impactful partnership needs to progress in a positive, jointly understood direction. We found that the most effective helpers often made sure this direction was full of possibility that was jointly imagined through partnership, not fixed at the start. In this way, possibilities can be mapped onto outcomes in terms of learning (see Outcomes).

Sometimes, parents’ visions for what they want were constrained by their sense of what is possible. Through careful questioning, and allowing the vision of possibility to evolve over time, some partnerships enabled families to end up in a space they wouldn’t have considered at the outset.

Possibility works best when it has both near and distant futures in view. The near future gives an immediate focus for things to work on. The distant future puts these efforts in context – why this all matters.

“Those little people are going to go to school one day. I think mum will be more confident to engage in their education … she will feel okay about inviting people over and having play dates so that her kids can have the most rich and meaningful life that’s available to them really. They can reach their potential ideally.” (Helper)

We found many instances of parents describing changes they didn’t think would be possible earlier on. For example, one mother who had been scared to take her child out was later making friends and interacting with other parents and children in a park.

This shows how helpers sometimes need to encourage parents to be bold or open-minded in their sense of possibility. However, helpers also have a responsibility to manage expectations in terms of short-term concrete outcomes.

Possibility works best when there is a dynamic balance between the achievable (soon) and the possible (in the future).

Re-imagining what is possible can focus on parents themselves, children, the family, and their relationship with the community.

a safe space for learning

Help, challenge and possibility have to exist in a safe space for learning

Help, challenge and possibility have to exist together in a relationally safe space. This means parents feel they can trust, and be open and honest with those helping them. From this space, parents, children and helpers can venture into the unfamiliar territory that learning inevitably brings with it.

However, a safe space doesn’t mean that parents feel comfortable all the time. We saw many instances where helpers had to ask difficult questions and take parents out of their comfort zone, for example, by responding differently to children’s cries or tantrums.

A safe space ultimately means protecting children. When there is a need to report safety concerns to other authorities, skilful practitioners do this in ways that are shared with parents and address their emotional needs.

Back to top | Back to essence of partnership overview | Next - Characteristics of impactful partnership

Using the essential ingredients to enhance your practice

The main worksheet is designed for practitioners to reflect on their practice. There is also a version that you may find helpful to use in your actual work with families - this contains the main figure and some key prompts.

Worksheet 1 (to print on A4 and complete by hand)

Combined resource and worksheet (can be completed in the digital file)